Many thanks to Remi Gai, Hannes Huitula, Giacomo Corrias, Avishay Yanai, Santiago Palladino, ais, ji xueqian, Brecht Devos, Maciej Kalka, Chris Bender, Alex, Lukas Helminger, Dominik Schmid, 0xCrayon, Zac Williamson for inputs, discussions, and reviews.

Contents

- Introduction: why we are here and why this article should exist

- Quick overview of each technology

- Client-side proving

- FHE

- MPC

- TEE

- Does it make sense to combine any of them and is it feasible?

- ZK-MPC

- MPC-FHE

- ZK-FHE

- ZK-MPC-FHE

- TEE-{everything}

- Conclusions: what to use and under what circumstances

- Comparison table

- What are the most reasonable approaches for on-chain privacy?

Prerequisites:

Introduction

Buzzwords are dangerous. They amuse and fascinate as cutting-edge, innovative, mesmerizing markers of new ideas and emerging mindsets. Even better if they are abbreviations, insider shorthand we can use to make ourselves look smarter and more progressive:

Using buzzwords can obfuscate the real scope and technical possibilities of technology. Furthermore, buzzwords might act as a gatekeeper making simple things look complex, or on the contrary, making complex things look simple (according to the Dunning-Kruger effect).

In this article, we will briefly review several suggested privacy-related abbreviations, their strong points, and their constraints. And after that, we’ll think about whether someone will benefit from combining them or not. We’ll look at different configurations and combinations.

Disclaimer: It’s not fair to compare the technologies we’re discussing since it won’t be an apples-to-apples comparison. The goal is to briefly describe each of them, highlighting their strong and weak points. Understanding this, we will be able to make some suggestions about combining these technologies in a meaningful way.

POV: a new dev enters the space.

Quick overview of each technology

Client-side ZKPs

Client-side ZKP is a specific category of zero-knowledge proofs (started in 1989). The exploration of general ZKPs in great depth is out-of-scope for this piece. If you're curious to learn about it, check this article.

Essentially, zero-knowledge protocol allows one party (prover) to prove to another party (verifier) that some given statement is true, while avoiding conveying any information beyond the mere fact of that statement's truth.

Client-side ZKPs enable generation of the proof on a user's device for the sake of privacy. A user makes some arbitrary computations and generates proof that whatever they computed was computed correctly. Then, this proof can be verified and utilized by external parties.

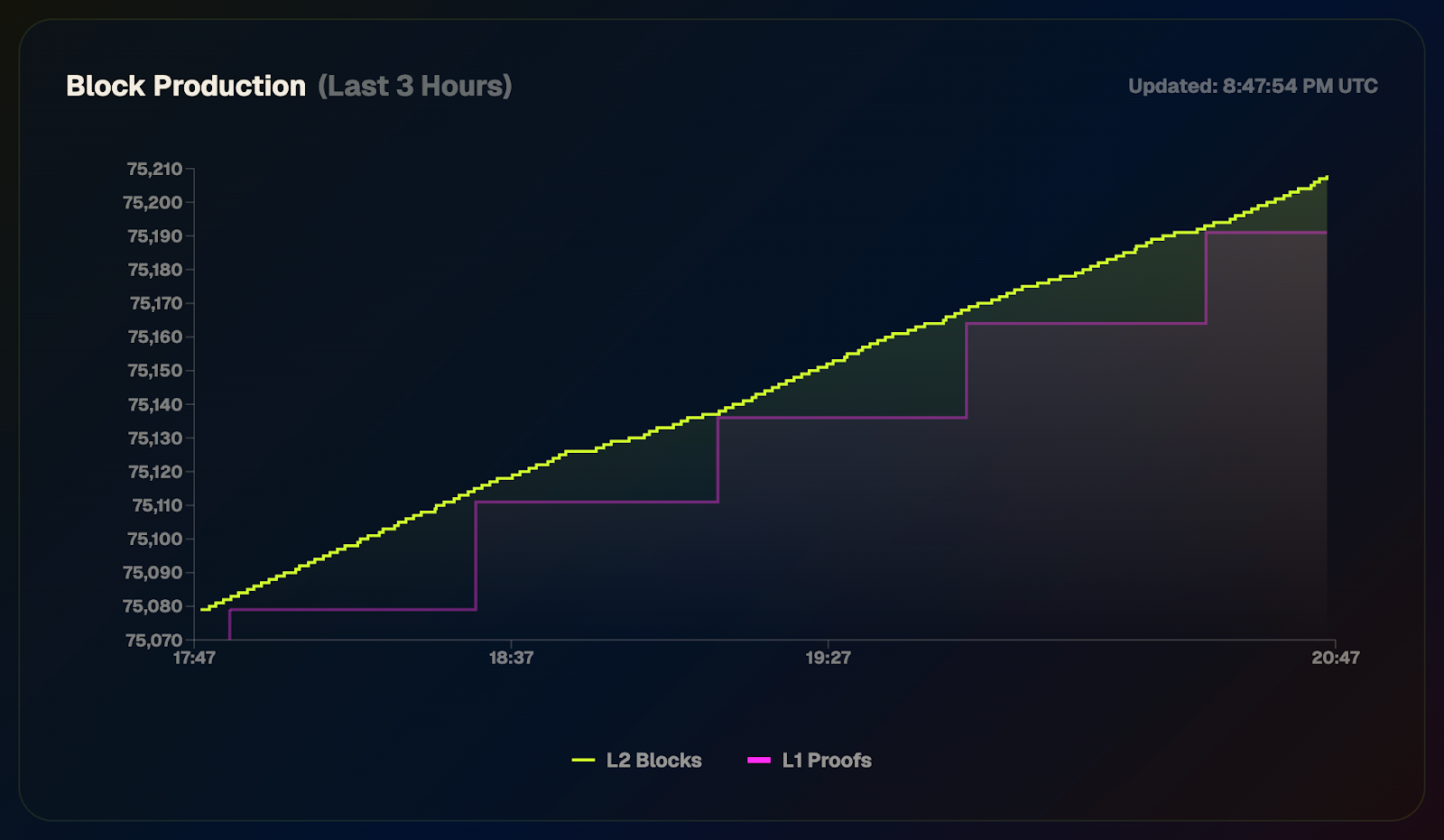

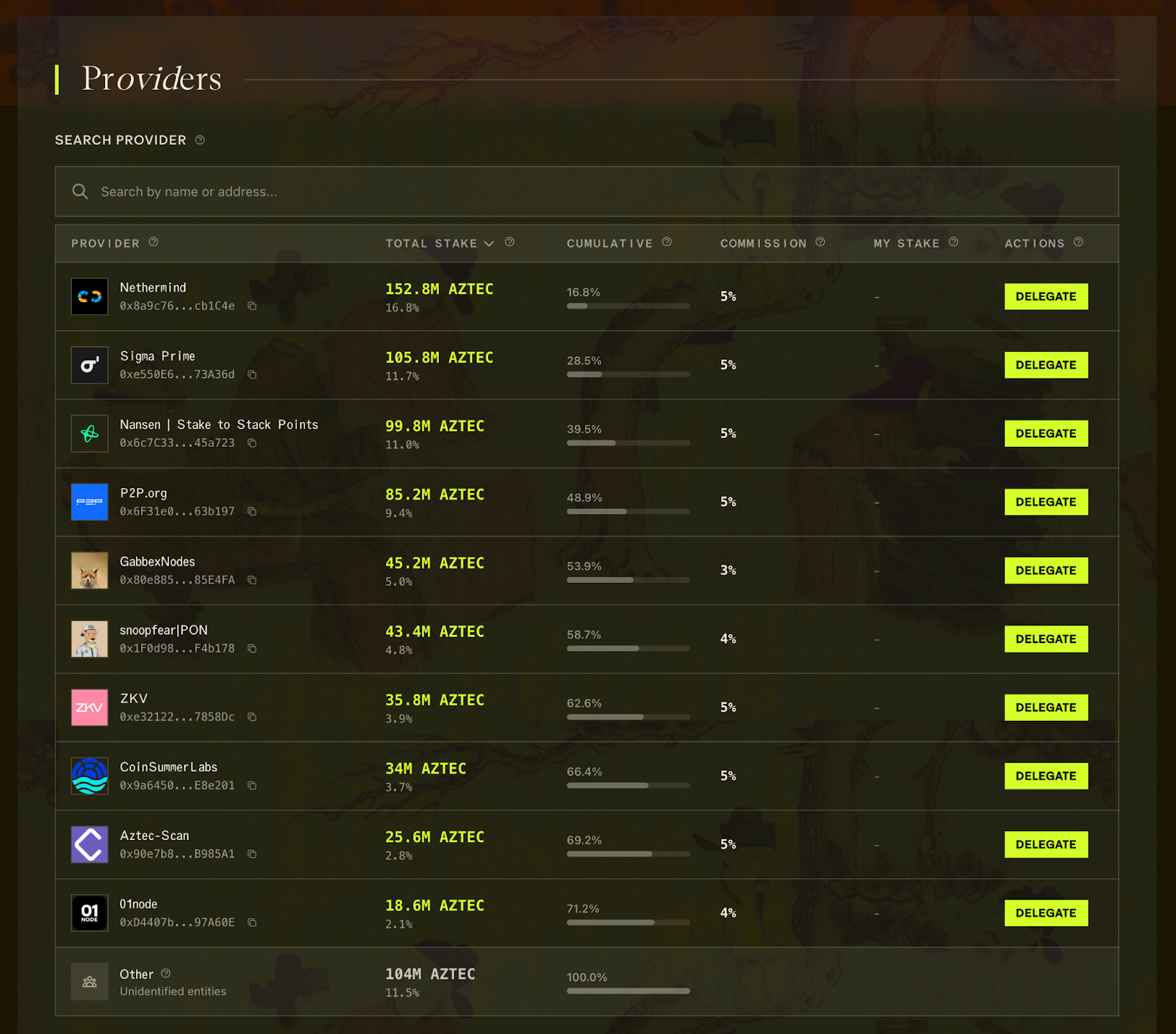

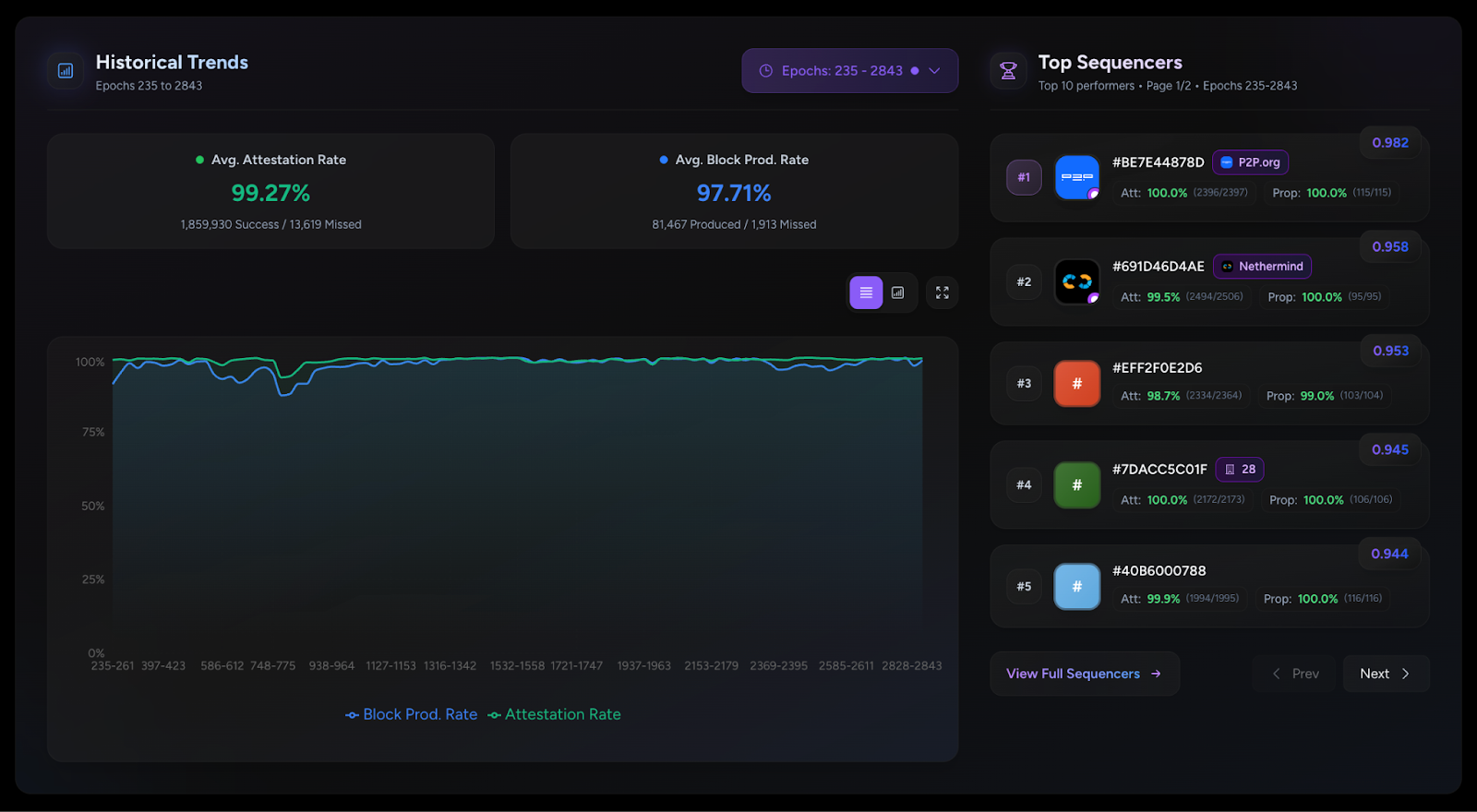

One of the most widely known use cases of the client-side ZKPs is a privacy preserving L2 on Ethereum where, thanks to client-side data processing, some functions and values in a smart-contract can be executed privately, while the rest are executed publicly. In this case, the client-side ZKP is generated by the user executing the transaction, then verified by the network sequencer.

However, client-side proof generation is not limited to Ethereum L2s, nor to blockchain at all. Whenever there are two or more parties who want to compute something privately and then verify each other’s computation and utilize their results for some public protocols, client-side ZKPs will be a good fit.

Check this article for more details on how client-side ZKPs work.

The main concern today about on-chain privacy by means of client-side proof generation is the lack of a private shared state. Potentially, it can be mitigated with an MPC committee (which we will cover in later sections).

Speaking of limitations of client-side proving, one should consider:

- The memory constraint: inherited from WASM memory cap – 4Gb and in case of mobile proving each device has its own memory cap as well.

- The maximum circuit size (derived from WASM memory cap): currently 2^20 for Aztec’s client-side proof generation (i.e. to prove any Noir program with Barretenberg in WASM).

What can we do with client-side ZKPs today:

- According to HashCloak benchmarking, a client-side ZKP of an RSA signature in Noir is generated in 0.2s (using UltraHonk and a laptop with Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-13700H CPU and 32 GB of RAM).

- According to Polygon Miden, a STARK ZKP for the Fibonacci calculator program for 2^20 cycles at 96-bit security level can be generated in 7 sec using Apple M1 Pro (16 threads).

- According to ZKPrize winners’ benchmarks, it takes 10 minutes to prove the target of 50 signatures over 100B to 1kB messages on a consumer device (Macbook pro with 32GB of memory).

Whom to follow for client-side ZKPs updates: Aztec Labs, Miden, Aleo.

MPC (Multiparty computation)

Disclaimer: in this section, we discuss general-purpose MPC (i.e. allowing computations on arbitrary functions). There are also a bunch of specialized MPC protocols optimized for various use cases (i.e. designing customized functions) but those are out-of-scope for this article.

MPC enables a set of parties to interact and compute a joint function of their private inputs while revealing nothing but the output: f(input_1, input_2, …, input_n) → output.

For example, parties can be servers that hold a distributed database system and the function can be the database update. Or parties can be several people jointly managing a private key from an Ethereum account and the function can be a transaction signing mechanism.

One issue of concern with MPCs is that one or more parties participating in the protocol can be malicious. They can try to:

- Learn private inputs of other parties;

- Cause the result of computations to be incorrect.

Hence in the context of MPC security, one wants to ensure that:

- All private inputs stay private (i.e. each party knows its input and nothing else);

- The output was computed correctly and each party received its correct output.

To think about MPC security in an exhaustive way, we should consider three perspectives:

- How many parties are assumed to be honest?

- The specific methods of corrupting parties.

- What can corrupted parties do?

How many parties are assumed to be honest?

Rather than requiring all parties in the computation to remain honest, MPC tolerates different levels of corruption depending on the underlying assumptions. Some models remain secure if less than 1/3 of parties are corrupt, some if less than 1/2 are corrupt, and some even have security guarantees even in the case that more than half of the parties are corrupt. For details, formal definition, and proof of MPC protocol security, check this paper.

The specific methods of corrupting parties

There are three main corruption strategies:

- Static – parties are corrupted before the protocol starts and remain corrupted to the end.

- Adaptive – parties can be corrupted at different stages of protocol execution and after execution remain corrupted to the end.

- Proactive – parties can switch between malicious and honest behavior during the protocol execution an arbitrary number of times, etc.

Each of these assumptions will assume a different security model.

What can corrupted parties do?

Two definitions of malicious behavior are:

- Semi-honest (also referred to as honest but curious, or passive adversary) – following the protocol as prescribed but trying to extract some additional information.

- Malicious – deviating from the protocol.

When it comes to the definition of privacy, MPC guarantees that the computation process itself doesn’t reveal any information. However, it doesn’t guarantee that the output won’t reveal any information. For an extreme example, consider two people computing the average of their salaries. While it’s true that nothing but the average will be output, when each participant knows their own salary amount and the average of both salaries, they can derive the exact salary of the other person.

That is to say, while the core “value proposition” of MPC seems to be very attractive for a wide range of real world use cases, a whole bunch of nuances should be taken into account before it will actually provide a high enough security level. (It's important to clarify the problem statement and decide whether it is the right tool for this particular task.)

What can be done with MPC protocols today:

When we think about MPC performance, we should consider the following parameters: number of participating parties, witness size of each party, and function complexity.

- According to the “Efficient Arithmetic in Garbled Circuits” paper, for general-purpose MPC, the computation costs are the following: at most O(n · ℓ · λ) bits per gate, with each multiplication gate using O(ℓ · λ) bits where ℓ is the bit length of values, λ is a computational security parameter, and n is the number of gates. A value can be translated from arithmetic to Boolean (and vice versa) at cost O(ℓ · λ) bits (e.g. to perform comparison operation).

- As a matter of illustration, we are also providing an example of a specialized MPC protocol:

According to dWallet Labs, their implementation of 2PC-MPC protocol (2-party ECDSA protocol) completes the signing phase in 1.23 and 12.703 seconds, for 256 and 1024 parties (emulating the second party in 2PC), respectively (claiming the number of parties can be scaled further).

- Worldcoin jointly with TACEO made a number of optimizations to existing Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) protocol, that enabled them to apply SMPC to the problem of iris code uniqueness. Early benchmarks show that one can achieve 10 iris uniqueness checks per second in ~6M database.

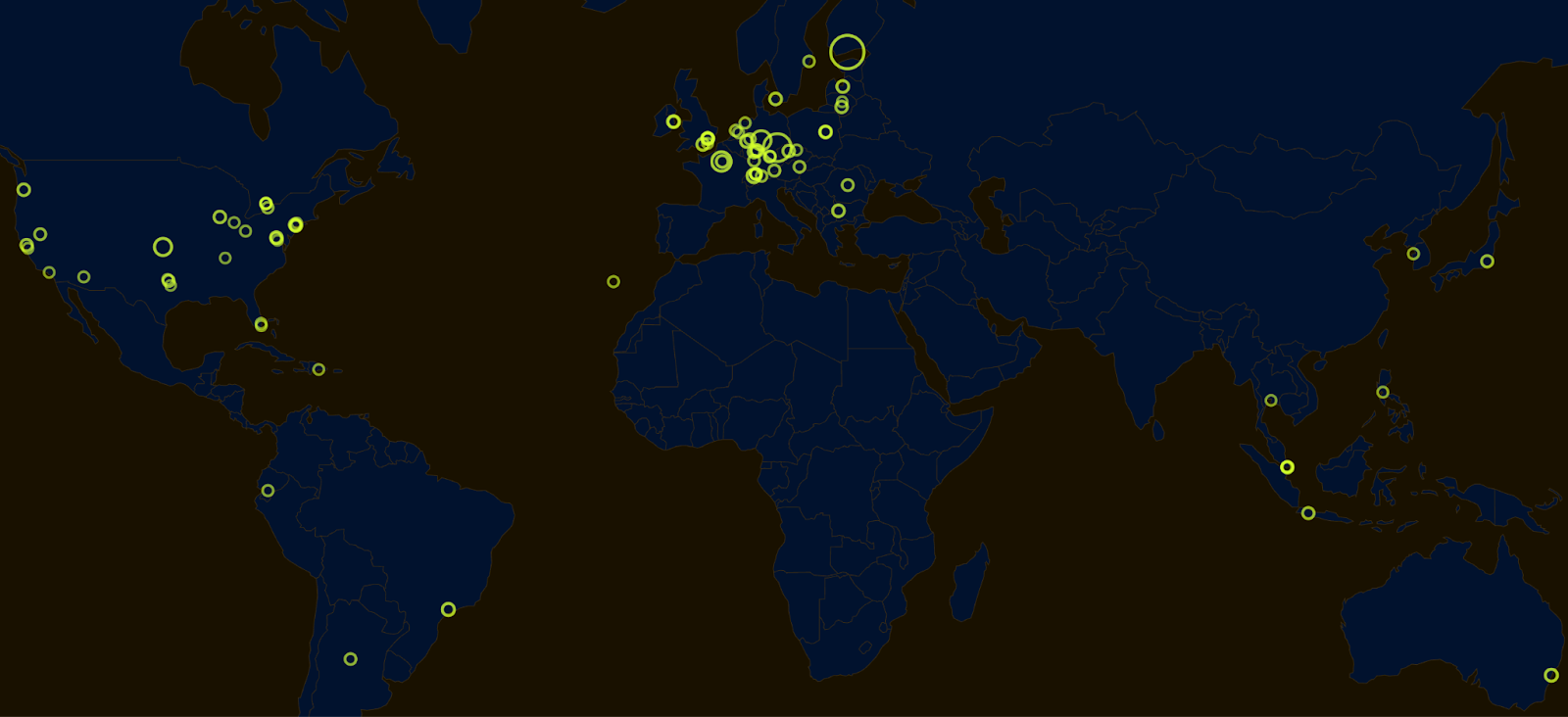

When it comes to using MPC in blockchain context, it’s important to consider message complexity, computational complexity, and such properties as public verifiability and abort identifiability (i.e. if a malicious party causes the protocol to prematurely halt, then they can be detected). For message distribution, the protocol relies either on P2P channels between each two parties (requires a large bandwidth) or broadcasting. Another concern arises around the permissionless nature of blockchain since MPC protocols often operate over permissioned sets of nodes.

Taking into account all that, it’s clear that MPC is a very nuanced technology on its own. And it becomes even more nuanced when combined with other technologies. Adding MPC to a specific blockchain protocol often requires designing a custom MPC protocol that will fit. And that design process often requires a room full of MPC PhDs who can not only design but also prove its security.

Whom to follow for MPC updates: dWallet Labs, TACEO, Fireblocks, Cursive, PSE, Fairblock, Soda Labs, Silence Laboratories, Nillion.

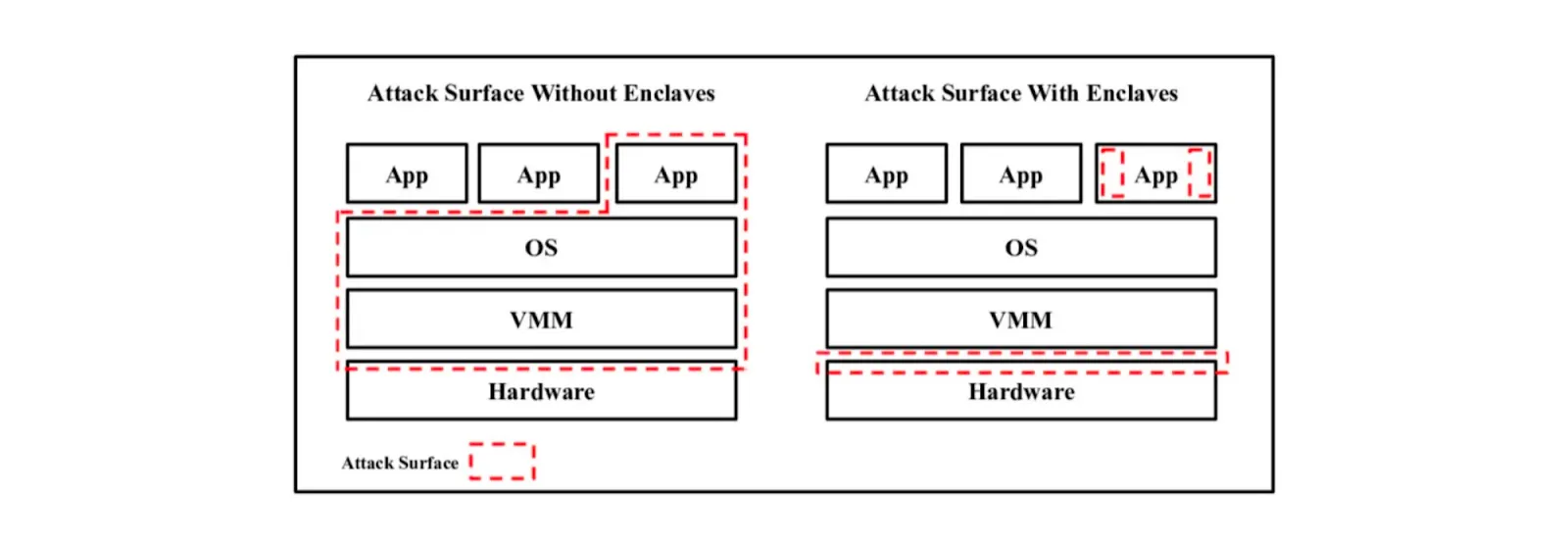

TEE

TEE stands for Trusted Execution Environment. TEE is an area on the main processor of a device that is separated from the system's main operating system (OS). It ensures data is stored, processed, and protected in a separate environment. One of the most widely known units of TEE (and one we often mention when discussing blockchain) is Software Guard Extensions (SGX) made by Intel.

SGX can be considered a type of private execution. For example, if a smart contract is run inside SGX, it’s executed privately.

SGX creates a non-addressable memory region of code and data (separated from RAM), and encrypts both at a hardware level.

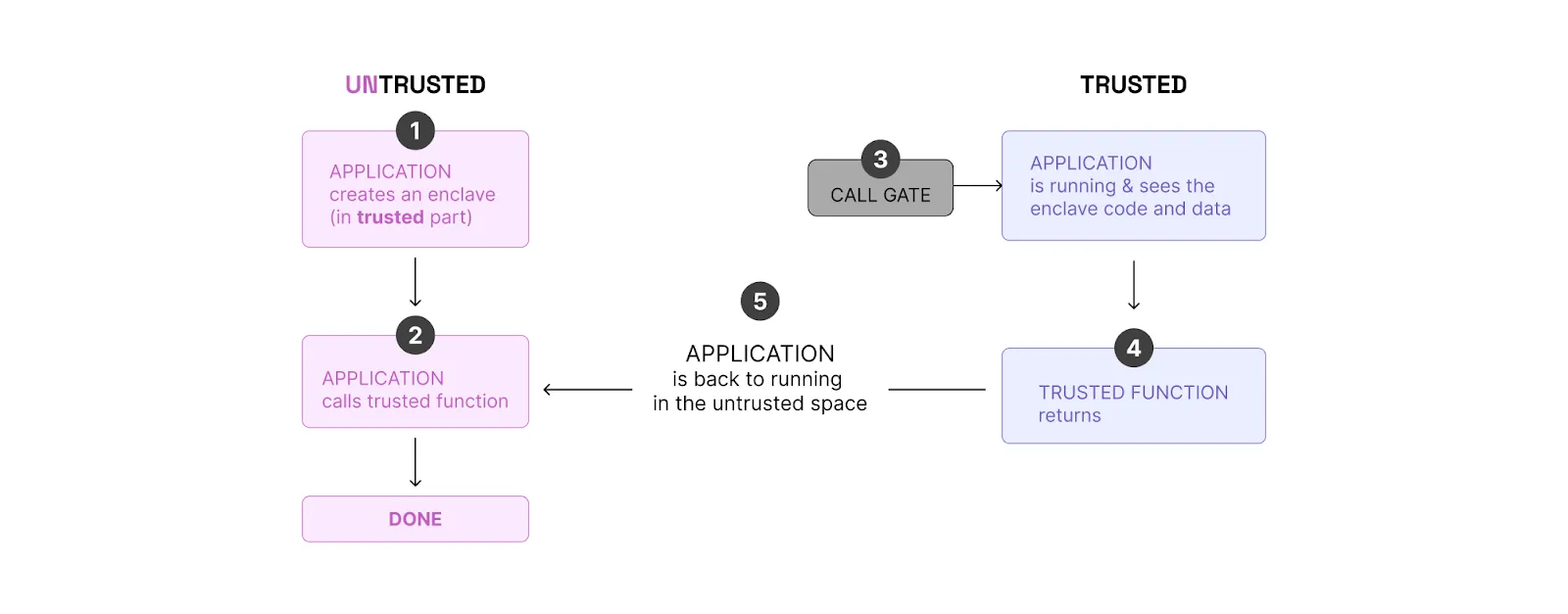

How SGX works:

- There are two areas in the hardware, trusted and untrusted.

- The application creates an enclave in the trusted area and makes a call to the trusted function. (The function is a piece of code developed for working inside the enclave.) Only trusted functions are allowed to run in the enclave. All other attempts to access the enclave memory from outside the enclave are denied by the processor.

- Once the function is called, the application is running in the trusted space and sees the enclave code and data as clear text.

- When the trusted function returns, the enclave data remains in the trusted memory area.

It’s worth noting that there is a key pair: a secret key and a public key. The secret key is generated inside of the enclave and never leaves it. The public key is available to anyone: Users can encrypt a message using a public key so only the enclave can decrypt it.

An SGX feature often utilized in the blockchain context is attestations. Attestation is the process of demonstrating that a software executable has been properly instantiated on a platform. Remote Attestation allows a remote party to be confident that the intended software is securely running within an enclave on a fully patched, Intel SGX-enabled platform.

Core SGX concerns:

- SGX is subject to side-channel attacks. Observing a program’s indirect effects on the system during execution might leak information if a program’s runtime behavior is correlated with the secret input content that it operates on. Different attack vectors include page access patterns, timing behavior, power usage, etc.

- Using SGX requires trusting Intel. Users must assume that everything is fine since the hardware is delivered with the private key already inside the trusted enclave.

- As a large enterprise, Intel is pretty slow in terms of patching new attacks. Check sgx.fail to find a list of publicly known SGX attacks that are yet to be fixed by Intel.

- Application developers who use SGX are dependent on specific hardware produced by Intel. The company might eventually decide to deprecate or significantly change all or specific versions in ways that might make some or all applications incompatible. Or even break them. For example in 2021, SGX was deprecated on consumer CPUs.

- It might be hard to detect cheating fast enough if it takes place in a private domain (like with SGX).

- In the case of a network relying purely on TEE for privacy (i.e. a number of nodes run inside TEE and each node has complete information), exploiting one node in the network is enough to exploit the whole network (i.e. leak secrets).

Speaking of SGX cost, the proof generation cost can be considered free of charge. Though if one wants to use remote attestations, the initial one-time cost (once per SGX prover) for it is in the order of 1M gas (to make sure the code in SGX is running in the expected way).

Onchain verification cost equals to verifying an ECDSA signature (~5k gas while for ZK signature verification will cost ~300k gas).

When it comes to execution time, there is effectively no overhead. For example, for proving a zk-rollup block, it will be around 100ms.

Where SGX is utilized in blockchain today:

- Taiko is running an execution client inside the SGX (utilizing TEE for integrity).

- Secret Network’s validators run their code inside a TEE (utilizing TEE for privacy).

- Flashbots are running SUAVE testnet on SGX.

Whom to follow for TEE updates: Secret Network, Flashbots, Andrew Miller, Oasis, Phala, Marlin, Automata, TEN.

FHE (Fully Homomorphic Encryption)

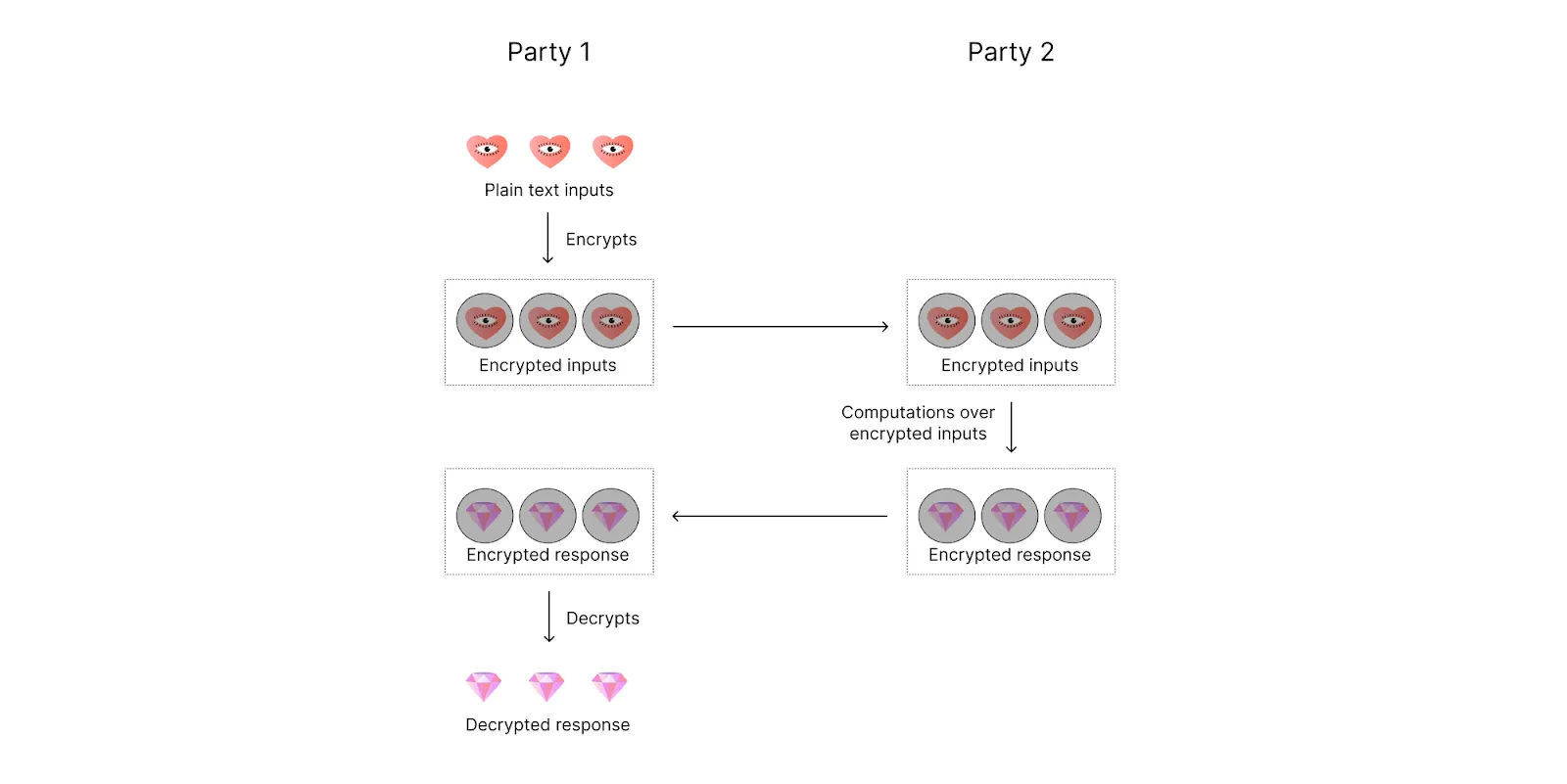

FHE enables encrypted data processing (i.e. computation on encrypted data).

The idea of FHE was proposed in 1978 by Rivest, Adleman, and Dertouzos. “Fully” means that both addition and multiplication can be performed on encrypted data. Let m be some plain text and E(m) be an encrypted text (ciphertext). Then additive homomorphism is E(m_1 + m_2) = E(m_1) + E(m_2) and multiplicative homomorphism is E(m_1 * m_2) = E(m_1) * E(m_2).

Additive Homomorphic Encryption was used for a while, but Multiplicative Homomorphic Encryption was still an issue. In 2009, Craig Gentry came up with the idea to use ideal lattices to tackle this problem. That made it possible to do both addition and multiplication, although it also made growing noise an issue.

How FHE works:

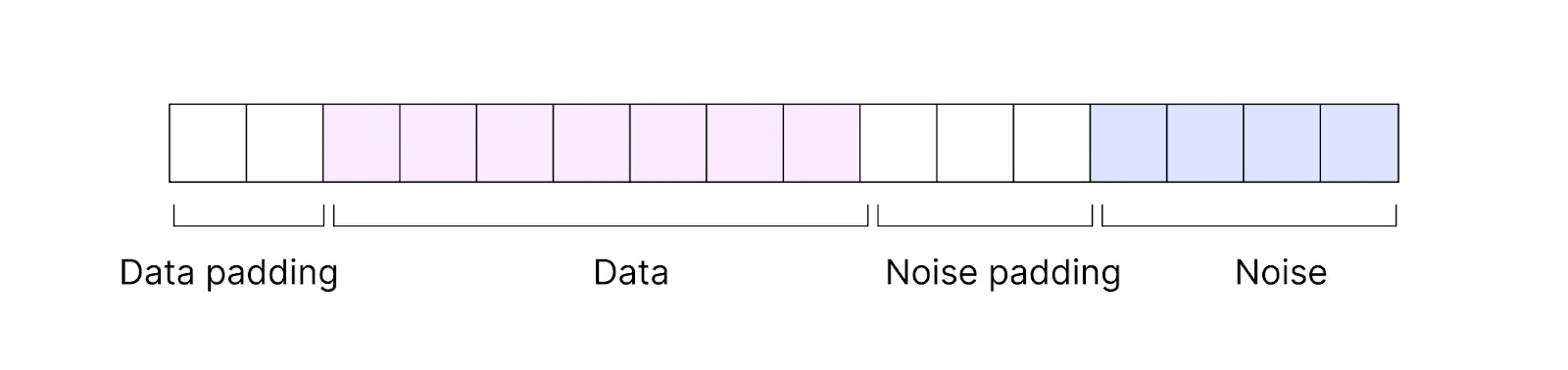

Plain text is encoded into ciphertext. Ciphertext consists of encrypted data and some noise.

That means when computations are done on ciphertext, they are done not purely on data but on data together with added noise. With each performed operation, the noise increases. After several operations, it starts overflowing on the bits of actual data, which might lead to incorrect results.

A number of tricks were proposed later on to handle the noise and make the FHE work more reliably. One of the most well-known tricks was bootstrapping, a special operation that reset the noise to its nominal level. However, bootstrapping is slow and costly (both in terms of memory consumption and computational cost).

Researchers rolled out even more workarounds to make bootstrapping efficient and took FHE several more steps forward. Further details are out-of-scope for this article, but if you’re interested in FHE history, check out this talk by mathematician Zvika Brakerski.

Core FHE concerns:

- If the user (who encrypts information) outsources computations to an external party, they have to trust that the computations were done correctly.

To handle the trust issue, (i) theoretically ZK can be used (though practically it’s not feasible today), (ii) economic consensus can be used. However, as FHE requires custom hardware (as computations to be done are very heavy), the number of participants in the FHE consensus network will always be limited, which is a problem for security.

- In the case of the FHE blockchain, there is one key for the whole network. Who holds the decryption key? The same will apply to dApps. For example, if an FHE computation modifies a liquidity pool total supply, that “total supply” must be decrypted at some point. But who possesses the key? (If you’re curious about FHE key attacks, check out this paper by Li and Micciancio).

- If an external party provides encrypted input, how can the party performing computations be sure that the external party knows the input and that the input was encrypted correctly? (This can be mitigated with zero-knowledge proof of knowledge, which will be discussed in the ZK-FHE section).

- While using FHE, one should ensure that the decrypted output doesn’t contain any private information that should not be revealed. Otherwise, formally it breaks privacy.

One should note that there are two different types of decryption: (i) to reveal the entire network (e.g. reveal cards at the end of the game), (ii) reencryption (i.e. decryption and encryption) as a view function (e.g. view your own cards). - FHE is “heavy.” When considering FHE computation cost (both in terms of computation volume and memory required), related considerations include (i) operations computation cost, (ii) communication cost, and (iii) evaluation keys size (a separate public key that is used to control the noise growth or the ciphertext expansion during homomorphic evaluation).

One might think about FHE hardware similar to Bitcoin hardware (highly performant ASICs).

Compared to computations on plain text, the best per-operation overhead available today is polylogarithmic [GHS12b] where if n is the input size, by polylogarithmic we mean O(log^k(n)), k is a constant. For communication overhead, it’s reasonable if doing batching and unbatching of a number of ciphertexts but not reasonable otherwise.

For evaluation keys, key size is huge (larger than ciphertexts that are large as well). The evaluation key size is around 160,000,000 bits. Furthermore, one needs to permanently compute on these keys. Whenever homomorphic evaluation is done, you’ll need to access the evaluation key, bring it into the CPU (a regular data bus in a regular processor will be unable to bring it), and make computations on it.

If you want to do something beyond addition and multiplication—a branch operation, for example—you have to break down this operation into a sequence of additions and multiplications. That’s pretty expensive. Imagine you have an encrypted database and an encrypted data chunk, and you want to insert this chunk into a specific position in the database. If you’re representing this operation as a circuit, the circuit will be as large as the whole database.

In the future, FHE performance is expected to be optimized both on the FHE side (new tricks discovered) and hardware side (acceleration and ASIC design). This promises to allow for more complex smart contract logics as well as more computation-intensive use cases such as AI/ML. A number of companies are working on designing and building FHE-specific FPGAs (e.g. Belfort).

“Misuse of FHE can lead to security faults.”

What can be done with FHE today:

- According to Ingonyama: With an LLM like GPT2, processing time for a single token is approximately 14.5 hours.

Token is a unit of text, for example, one english word ≈ 1.3 tokens. Each text request to GPT2 consists of a number of tokens. Based on the processing time of one token, one can define the processing time of the whole request.

With parallel processing, deploying 10,000 machines, the time is 5 seconds/token. With a custom ASIC designed, the time can be decreased to 0.1 second/token, but this would require huge initial investments in data centers and ASIC design. - According to Zvika Brakerski: When asked the question “Can we build production-level systems where FHE brings value?” he responds, “I don’t know the answer yet.”

- According to Zama: A toy-implementation of Shazam (a music recognition app) with Zama FHE library takes 300 milliseconds to recognize a single song out of 1,000. But how will that change as the database grows? (The real Shazam library has 45M songs.)

- According to Inco, FHE is usable today for simple blockchain use cases (i.e. smart contracts with simple logics). For example, in a confidential ERC-20 transfer that’s FHE-based, you are performing an FHE addition, subtraction, comparison, and conditional multiplexer (cmux/select) to update the balances of the sender and recipient. With CPU, Inco can do 10 TPS, and with GPU – 20-30 TPS.

Note: In all of these examples, we are talking about plain FHE, without any MPC or ZK superstructures handling the core FHE issues.

Whom to follow for FHE updates: Zama, Sunscreen, Zvika Brakerski, Inco, FHE Onchain.

Does it make sense to combine any of these, and is doing so feasible?

As we can see from the technology overview, these technologies are not exactly interchangeable. That said, they can complement each other. Now let’s think. Which ones should be combined, and for what reason?

Disclaimer: Each of the technologies we are talking about is pretty complex on its own. The combinations of them we discuss below are, to a large extent, theoretical and hypothetical. However, there are a number of teams working on combining them at the time of writing (both research and implementation).

ZK-MPC

In this section, we mostly describe two papers as examples and don’t claim to be exhaustive.

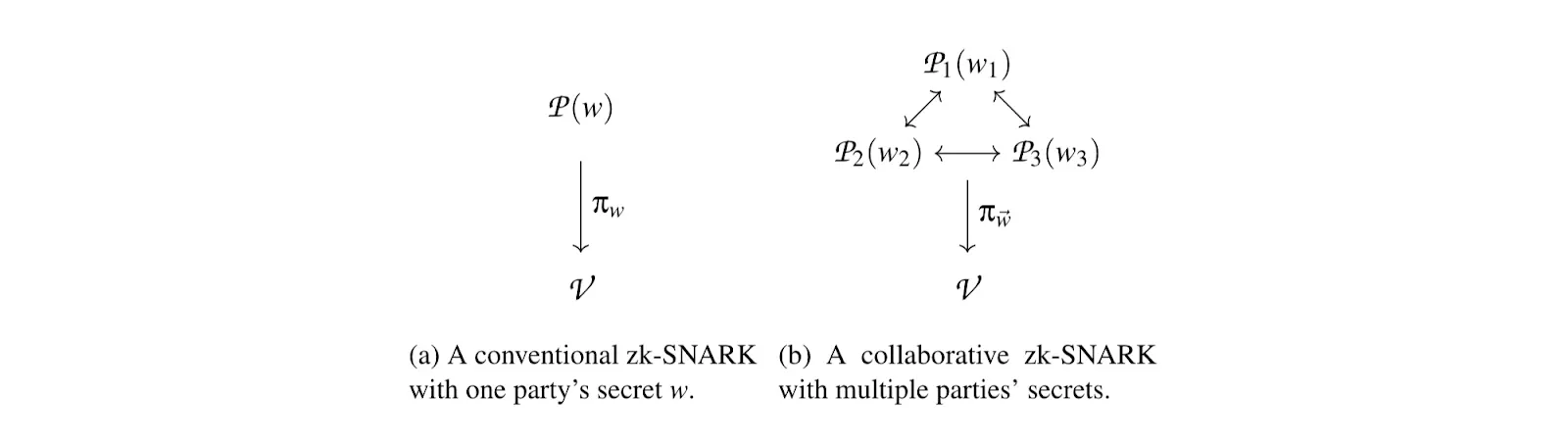

One of the possible applications of ZK-MPC is a collaborative zk-snark. This would allow users to jointly generate a proof over the witnesses of multiple, mutually distrusting parties. The proof generation algorithm is run as an MPC among N provers where function f is the circuit representation of a zk-SNARK proof generator.

Collaborative zk-SNARKs also offer an efficient construction for a cryptographic primitive called a publicly auditable MPC (PA-MPC). This is an MPC that also produces a proof the public can use to verify that the computation was performed correctly with respect to commitments to the inputs.

ZK-MPC introduces the notion of MPC-friendly zk-SNARKs. That is to say, not just any MPC protocol or any zk-SNARK can feasibly be combined into ZK-MPC. This is because MPC protocols and zk-SNARK provers are each thousands of times slower than their underlying functionality, and their combination is likely to be millions of times slower.

For those familiar with elliptic curve cryptography, let’s think for a moment about why is ZK-MPC tricky:

If doing it naively, you could decompose an elliptic curve operation into operations over the curve’s base field; then there is an obvious way to perform them in an MPC. But curve additions require tens of field operations, and scalar products require thousands.

The core tricks suggested for use include:

- MPC techniques applied directly to elliptic curves to make curve operations cheap.

- The N shares are themselves elliptic curve points, and the secret is reconstructed by a weighted linear combination of a sufficient number of shares.

- An optimized MPC protocol is utilized for computing sequences of partial products.

Essentially, ZK-MPC in general and collaborative zk-SNARKs in particular are not just about combining ZK and MPC. Getting these two technologies to work in concert is complex and requires a huge chunk of research.

According to one of the papers on this topic, for collaborative zk-SNARKs, over a 3Gb/s link, security against a malicious minority of provers can be achieved with approximately the same runtime as a single prover. Security against N−1 malicious provers requires only a 2x slowdown. Both TACEO and Renegade (launched mainnet on 04.09.24) teams are currently working on implementing this paper.

Another application of ZK-MPC is delegated zk-SNARKs. This enables a prover (called a delegator) to outsource proof generation to a set of workers for the sake of efficiency and engaging less powerful machines. This means that if at least one worker does not collude with other workers, no private information will be revealed to any worker.

This approach introduces a custom MPC protocol. The issues with using existing protocols are:

- Existing state-of-the-art MPC protocols achieving malicious security against a dishonest majority of workers rely on relatively heavyweight public-key cryptography, which has a non-trivial computational overhead.

- These MPC protocols require expressing the computation as an arithmetic circuit, including expressing complex operations such as elliptic curve multi-scalar multiplications and polynomial arithmetic that is expensive.

One of the papers on this topic suggests using SPDZ as a starting point and modifying it. A naive approach would be to use the zk-SNARK to succinctly check that the MPC execution is correct by having the delegator verify the zk-SNARK produced by the workers. However, this wouldn’t be knowledge-sound because the adversary can attempt to malleate its shares of the delegator’s valid witness (w) to produce a proof of a related statement. Even if the resulting proof is invalid, it can leak information about w. However, we can use the succinct verification properties of the underlying components of the zk-SNARK, the PIOP (Polynomial Interactive Oracle Proof) and the PC (Polynomial Commitment) scheme.

Other modifications correspond to optimizations, such as optimizing the number of multiplications in, and the multiplicative depth of circuits for these operations; and introducing a consistency checker for the PIOP to enable the delegator to efficiently check that the polynomials computed during the MPC execution are consistent with those that an honest prover would have computed.

According to one of the papers on this topic, “... when compared to local proving, using our protocols to delegate proof generation from a recent smartphone (a) reduces end-to-end latency by up to 26x, (b) lowers the delegator’s active computation time by up to 1447x, and (c) enables proving up to 256x larger instances.”

For a privacy-preserving blockchain, ZK-MPC can be utilized for collaboratively proving the correctness of state transition, where each party participating in generating proof has only a part of the witness. Hence the proof can be generated while no single party is aware of what they are proving. For this purpose, there should be an on-chain committee that will generate collaborative zk-SNARKs. It’s worth noting that even though we are using the term “committee,” this is still a purely cryptographic solution.

Whom to follow for ZK-MPC updates: TACEO, Renegade.

MPC-FHE

There are a number of ways to combine FHE and MPC and each serves a different goal. For example, MPC-FHE can be employed to tackle the issue “Who holds the decryption key?” This is relevant for an FHE network or an FHE DEX.

One approach is to have several parties jointly generate a global single FHE key. Another approach is multi-key FHE: the parties take their existing individual (multiple) FHE key pairs and combine them in order to perform an MPC-like computation.

As a concrete example, for an FHE network, the state decryption key can be distributed to multiple parties, with each party receiving one piece. While decrypting the state, each party does a partial decryption. The partial decryptions are aggregated to yield the full decrypted value. The security of this approach holds under an assumption of 2/3 honest validators.

The next question is, “How should other network participants (e.g. network nodes) access the decrypted data?” It can’t be done using a regular oracle (i.e. each node in the oracle consensus network must obtain the same result given the same input) since that would break privacy.

One possible solution is a two-round consensus mechanism (though this relies on social consensus, not pure cryptography). The first round is the consensus on what should be decrypted. That is, the oracle waits until most validators send it the same request for decryption. Next, the round of decryption. Then, the validators update the chain state and append the block to the blockchain.

Whom to follow for MPC-FHE updates: Gauss Labs (utilized by Cursive team).

ZK-FHE

MPC-FHE has two issues that can potentially be mitigated with ZK:

- Were inputs encrypted correctly?

- Were the computations on encrypted data performed correctly?

Without introducing ZK, both issues listed above make one fragment of private computations unverifiable. (That doesn’t quite work for most blockchain use cases).

Where are we today with ZK-FHE?

According to Zama, proof of one correct bootstrapping operation can be generated in 21 minutes on a huge AWS machine (c6i.metal). And that’s pretty much it. Hopefully, in the upcoming years we will see more research on ZK-FHE.

Whom to follow for ZK-FHE updates: Zama, Pado Labs.

ZK-MPC-FHE (a sum of MPC-FHE and ZK-FHE)

One issue with MPC-FHE we haven’t mentioned so far has to do with knowing for sure that an encrypted piece of information supplied by a specific party was encrypted by that same party. What if party A took a piece of information encrypted by party B and supplied it as its own input?

To handle this issue, each party can generate a ZKP that they know the plaintext they are sending in an encrypted way. Adding this ZK tweak with two ZK tweaks from the previous section (ZK-FHE), we will get verifiable privacy with ZK-MPC-FHE.

Whom to follow for ZK-MPC-FHE updates: Pado Labs, Greco.

TEE-{everything}

TL;DR: In general, when it comes to using any new technology, it makes sense to run it inside TEE since the attack vector with TEE is orders of magnitude smaller than on a regular computer:

Using TEE as an execution environment (to construct ZK proofs and participate in MPC and FHE protocols) improves security at almost zero cost. In this case, secrets stay in TEE only within active computation and then they are discarded. However, using TEE for storing secrets is a bad idea. Trusting TEEs for a month is bad, trusting TEEs for 30 seconds is probably fine.

Another approach is to use TEE as a “training wheels,” for example, for multi-prover where computations are run both in a ZK circuit and TEE, and to be considered valid they should agree on the same result.

Whom to follow for TEE-{something} updates: Safeheron (TEE-MPC).

Conclusions: should we combine them all?

It might feel tempting to take all of the technologies we’ve mentioned and craft a zk-mpc-fhe-tee machine that will combine all their strengths:

However, the mere fact that we can combine technologies doesn’t mean we should combine them. We can combine ZK-MPC-FHE-TEE and then add quantum computers, restaking, and AI gummy bears on top. But for what reason?

Each of these technologies adds its own overhead to the initial computations. 10 years ago, the blockchain, ZK, and FHE communities were mostly interested in proof of concept. But today, when it comes to blockchain applications, we are mostly interested in performance. That is to say we are curious to know if we combine a row of fancy technologies, what product/application could we build on it?

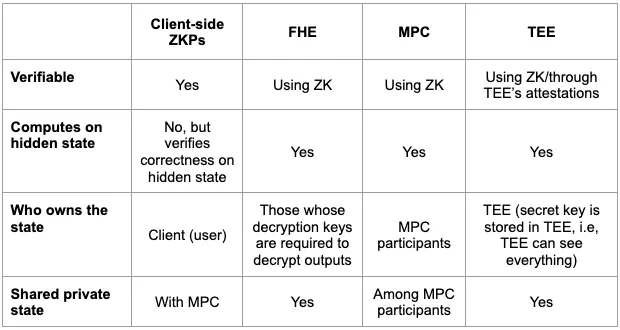

Let’s structure everything we discussed in a table:

Hence, if we are thinking about a privacy stack that will be expressive enough that developers can build any Web3 dApps they imagine, from everything we’ve mentioned in the article, we either have MPC-ZK (MPC is utilized for shared state) or ZK-MPC-FHE. As for today, client-side zero-knowledge proof generation is a proven concept and we are currently at the production stage. The same relates to ZK-MPC; a number of teams are working on its practical implementation.

At the same time, ZK-MPC-FHE is still at the research and proof-of-concept stage because when it comes to imposing zero-knowledge, it’s know how to zk-prove one bootstrapping operation but not arbitrary computations (i.e. circuit of arbitrary size). Without ZK, we lose the verifiability property necessary for blockchain.

Sources:

- A paper, “Secure Multiparty Computation (MPC)” by Yehuda Lindell.

- An article, “Introduction to FHE: What is FHE, how does FHE work, how is it connected to ZK and MPC, what are the FHE use cases in and outside of the blockchain, etc.”

- A talk, “Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) for Blockchain Applications” by Ari Juels.

- An article, “Why multi-prover matters. SGX as a possible solution.”

- A paper, “Experimenting with Collaborative zk-SNARKs: Zero-Knowledge Proofs for Distributed Secrets” by Alex Ozdemir and Dan Boneh.

- A paper, “EOS: Efficient Private Delegation of zkSNARK Provers” by Alessandro Chiesa, Ryan Lehmkuhl, Pratyush Mishra, and Yinuo Zhang.

- A paper, “Practical MPC+FHE with Applications in Secure Multi-Party Neural Network Evaluation” by Ruiyu Zhu, Changchang Ding, and Yan Huang.

- An article, “Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Interpolating between MPC and FHE”

- A talk, “Building Verifiable FHE using ZK with Zama.”

- An article, “Client-side Proof Generation.”

- An article, “Does zero-knowledge provide privacy?”